|

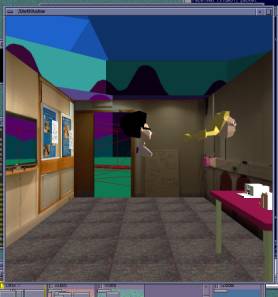

A user's view of the Equator Mackintosh Room demo |

|

|

Phil Stenton (doc) The following is a description of the experience of being the 'real' visitor in a scenario aimed at exploring the technical and HCI issues of creating a feeling of co-presence between a 'real' and virtual visitor to a room in a museum. Further discussion is included based on observations from within the virtual space. The Scenario: Visiting a gallery with a virtual friendFirst, my prejudices and biases out in the open. I must admit to still finding the scenario of a visit to a gallery less than compelling but this is more to do with the gallery venue than the idea of sharing of experiences across real and virtual spaces. I believe strongly in the value of sharing experiences remotely. I have previously worked on discourse analysis for remote, synchronous collaboration and have a PhD in the area of computational models of stereo-vision (it's a bit old now though). The visit to the Reactor was my first such experience; I have probably experienced most other forms of stereo presentation.

(A view of the virtual representation of the shared room showing the avatars of both visitors.) The experience and the scienceThe demo was immediately impressive on two counts. The experience co-presence, though limited, was enough to convey the intent and generate excitement for the promise of a more immersive sharing experience built on the results of the demonstration. The second impressive feature was the integration that took place over less than a week to create a substantial demonstration of the vision or real and virtual co-presence. Cues for co-presenceThe effectiveness of the eventual Mack' room demonstration will hinge on the strength of the co-presence cues and the social acceptability of the behaviour of the real visitor in the context of a gallery visit. Clearly, mobile phone behaviour is not in the category of acceptable volumes for gallery conversations. The conversations will have to be lot less intrusive in a public space. The cues demonstrated in this first prototype system were audio and visual. The one audio cue was a mobile phone link with a hands free connection. Participants in the real and virtual versions of the room could talk to each other describing their parallel environments. Audio was used for voice communication, which mainly centered on coordination activities. Shared sounds were not generated between the environments. Three visual cues were available within both the real environment and the virtual environments. In the real environment the virtual visitor could be seen by the 'real' visitor as an icon ( an isosceles triangle) on a hand-held display superimposed on a floor plan of the room . Both real and virtual visitors were represented in this way. The orientation of each visitor was represented by the direction of the apex of each triangle. In the virtual world the 'real' visitor could be seen as an avatar standing in a position in the virtual room corresponding to the same position in the real room. Location information was provided by ultrasonic sensing in the real room. Both real and virtual rooms contained a digital window. In the real room this was a large monitor displaying the virtual world. When the visitor in the virtual world stood by the window outside the room their avatar could be seen 'in the window'. When the 'real' visitor stood by the window but inside the room the virtual visitor outside could see a video image of the 'real' visitor (provided by a camera above the large monitor).

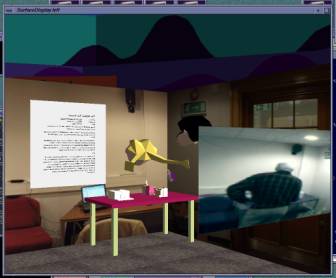

(This picture is taken from inside the virtual world and shows the avatars of both visitors looking at items on the table. The page of writing and video picture look to be floating in space because this viewpoint looks through the nearside wall. The video image is the view through the digital window from the virtual side. Note Cliff can be seen as the avatar with the pigtails and in 'video reality' through the digital window.) The third visual cue for both visitors was provided by the one to one mapping of the real and virtual rooms; the virtual room being (almost) an exact replica of the real room. Critique..The first thing to note was the dominance of the audio for coordinating activity between the two visitors. The hand-held floor map display was used initially in my case because it was there and the first object described as I was kitted out for the demo. As soon as the audio connection (which had no directionality) was established that took over for choreographing our movements. Like astronauts in a weightless environment clinging to objects we used deixis to 'pull ourselves together' (Can you see the writing on this poster? Are you in front of that box or this one?). These initial dialogues may not be representative of the final experience where a quick glance at the display to see where your virtual partner is may be more appropriate and socially acceptable. Clearly our dialogue was one of discovering the shared experience rather than sharing the visit. A defining moment for me was the request from my virtual partner, “Get out of the way I can't see the poster.” At this point it felt like we were in the same room rather than sharing information about two identical rooms in different places. The digital window proved to be a pleasing experience. Having talked to my virtual friend and discussed possible co-locations it was good to see their 'face' in the digital window. It may have been the simple face of an avatar but it was confirmation that we were sharing the same space. I had thought the window could have been placed in the middle of the room as it is in the Mixed-Reality Lab then the virtual person would not have to leave the room to look back inside. At this point a better idea was suggested, to create a mirror instead of a window (Bill Gaver), then both visitors could stand the same side. Building on the mirror idea, reflections could be created in most glass-mounted exhibits either through LCD overlays (expensive and requires new infrastructure in the gallery) or projections from light sources carried by the real visitor. The point about these reflections is they don't have to be high-resolution renderings, just an inverse shadow effect. The floor plan displayed on the JornadaThe floor plan of the room displayed on the Jornada was confusing. When people navigate using maps they are split in their preference of orientation of the map. Some people have to turn the map around until it is consistent with the way they are facing (I'm sure there is a popular reference for this). This task is not a map reading task. The goal of the Jornada display is to act as a cue to the presence of the other person. The movement of both the 'radar' blips representing the two people makes this task much more of a sensory motor task than reading a map. When holder of the display moves forward the triangle representing them should move forward against the floor plan not sideways. Such motion transformations are not used in any feedback system I have come across. A simple solution would be to remove the floor plan altogether. The proximity cue is provided by the spatial relationship between the two people icons (triangles). The previous radar display demonstrated at Nottingham would have sufficed with one addition that the boundary of the display corresponds to the boundary of the room. This should be sufficient to provide the 'real' visitor with enough information to judge the absolute proximity of the virtual visitor. In previous discussions we have contemplated the scenario where the two visitors become separated, walking into different rooms, onto different floors or into different streets. In the first two cases the audio contact is probably sufficient to reconnect. In the street example a zoom out and street map overlay facility may be necessary. One final small point on the display would be to suggest that the triangles are replaced by a circle and nose line, thus o-. ( I hesitate to mention this as it is a minor implementation detail and I appreciate the triangles were born out of the pragmatics of the system rather than deep design.) Audio potentialClearly there is a great opportunity to increase the sense of shared space through the audio channel. Directional audio is one obvious place to start. The volume and direction of the virtual visitor's voice, the sound of footsteps on the polished wood floors of the Mack' room, the sharing of incidental and ambient sounds would all add to the common experience and the sense of co-presence. If the virtual person taps on a glass display case both visitors should hear the sound just as the footsteps of the 'real' visitor should be spatially registered with the corresponding avatar in the virtual room. My guess is that the dominance of the audio together with careful positioning of digital mirrors and reflectors the handheld display will become redundant. The future of the hand-held displayOne way to revive its utility would be to turn it into a mobile digital window which when held up between the real and virtual visitor acts in the same way as the screen in the demonstration. Showing the avatar to the real visitor and a video image to the virtual visitor. Cliff has suggested using his digital lens to frame video camera images for the virtual visitor in a reversal of its originally intended use. Location cues in the virtual worldHaving observed virtual visitors in the Reactor I was very impressed with the realism of the virtual room but confused by the registration of real and virtual locations. Inside the room everything was mapped one to one. Outside the room I wasn't sure whether things were. What follows is what I would have expected: As the virtual visitor I step into the Reactor and see a typically virtual Reactor-like environment with its own landmarks. I then move through the virtual door corresponding to the one I used to enter, travel through the reactor's anteroom and into the museum room. If I look back from the Reactor's anteroom into the virtual Reactor I see the initial Reactor environment with the same starting landmarks just as if it were a real room with its unchanging appearance. In this way my spatial frame of reference is never violated. This maybe a luxury afforded because of the close proximity of the two rooms and as such maybe impossible to scale. A virtual viewer in London would not want to spend hours on a virtual train to Glasgow before entering the Mack' room but a sequence starting from a virtual representation of the real Reactor room and moving out via some mode of rapid transport to the destination location (i.e. walking through a digital portal) would help the feeling of going there from here. Co-presence and parallels in the world of video conferencingIn the late 1980's a number of studies were published investigating the value of video conferencing and the elements that helped or hindered communication and the feeling of co-presence. Many studies failed to show that 'talking heads' was of significant value to warrant the cost of teleconferencing systems. Bandwidth issues interrupted the flow of conversation and an inability to focus visual attention without expert camerawork created a feel of we are here and you are there rather than we are all in the same meeting. Telephone conferences were no better at providing co-presence but enjoyed greater success because expectations were correctly set (in video conferencing participants were seduced into making incorrect assumptions about the availability of visual communication cues). One of the main lessons from these studies was that the most valuable thing to view during remote conferencing is the subject of the conversation to support the use of deixis (pointing to this and that, over here and there). Two lessons can be learned from the work on video conferencing: pointing is important and should be supported (the avatar hands in the demo are currently large and inarticulate) and systematic study of the cues that add to or detract from the feeling of co-presence is well worth the investment. The bench mark for the Mack' room is mobile phone communication and a video camera. A potential progression of cues might be to increase the number and type of audio and visual cues to create combinations that optimise co-presence Audio cues Visual cues Phone - voice Video camera Directional voice Reactor (Virtual model) Directional movement sounds Hand-held radar display Directional tapping sounds Reflections/ Digital mirror Digital window Hand-held Digital lens The last thing to say is that video conferencing may turn out to have been an easier space to map. Mobile interfaces between real and virtual worlds have many more situational contexts to consider. This also makes it more interesting and potential much more significant. |

|