CF1 Lecture Notes - Part 2

W P Cockshott

Table

of Contents

2.1 Block Diagram of Typical Computer

2.2 Input/output (I/O) Subsystem

2.3 Memory-mapped I/O Structure

2.5 Typical Structure of Main Memory

3 Programming Model for the 8086

Map of the first megabyte of PC memory

You can obtain help by typing a ?

Tutorial on protected mode addressing

Instruction Repertoire - types of operation

[label] DB initialvalue [,initialvalue]

10 I8086 Assembler Program: Global View

Assembler Directives (aka Pseudo-ops)

Assembly Language Instructions

11 Pseudo-Ops or Assembler Directive Mnemonics

12 Opcode or Instruction Mnemonics

13 Format of Assembly Language Statements

14 INTRODUCTION TO I8086 A.L.P.

Base-indexed with displacement

16 Addressing Modes and Operands

17 Code generation for 8x86 processors

Low Level Program Control Structures

Second practical for Assembler Level

Programming

Appendix a The abstract machine

AppendiX B Predefined PC Hardware and Software

Interrupts

1.1.1

Figures

Figure 1 abstract diagram of

computer

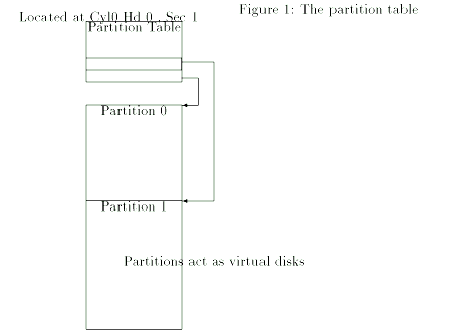

Figure 5 Disk

Surface being written

Figure 6 FM

disk encoding used in early floppies

• Figure 7

MFM encoding used in modern floppies

Figure 8

Partitions and partition table

Figure 9

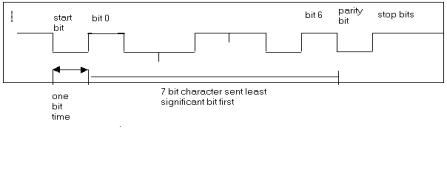

synchronoous serial packet

Figure 10

Asynchronous serial transmission

Figure 11 stack after entry to ISR in 32-bit

mode

Figure 12 stack after entry to ISR in 16-bit

mode

1.1.2

2.1 Block Diagram of Typical Computer

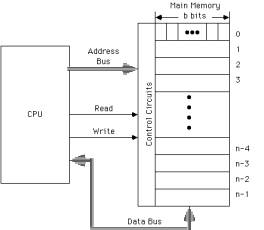

Figure 1 abstract diagram of computer

2.2 Input/output (I/O) Subsystem

Figure 2 i/o subsystem

2.3 Memory-mapped I/O Structure

Figure 3Memory mapped I/O

2.4 Memory Structure

Most, if not all, modern day computers incorporate at least two types of main memory device - Read Only Memory (ROM) and Random Access Memory (RAM).

2.4.1 Read Only Memory (ROM)

This type of memory, as its name suggests, can only be read from. More importantly, the contents of such memory devices are non-volatile which means that their contents are not lost when the power is switched off. This is a necessary requirement to be able to ‘boot’ (start from a power off state) a computer as it must get (at least) its first few instructions from such a device. The (rest of the) operating system is then, typically, loaded from a magnetic media such as tape, floppy disk or hard disk. Some computers keep the whole of their operating system in ROM although this has the disadvantage that it cannot be as easily updated as changing the (contents of) magnetic media.

2.4.2 Random Access Memory (RAM)

more accurately called Read/Write Memory (RWM) - the contents of which can be written as well as read. However, it is, more often than not, volatile in that it loses its contents when power is switched off. Most computers have much more RAM than ROM as most programs, including the operating system, are loaded into this type of memory.

2.5 Typical Structure of Main Memory

Figure 4Main memory

2.6 Memory Organisations

7......0 15......8 7......0 15......8 7......0

-------- ----------------- -----------------

0 1 | 0 0 | 1

-------- ----------------- -----------------

1 3 | 2 2 | 3

-------- ----------------- -----------------

2 5 | 4 4 | 5

-------- ----------------- -----------------

3 7 T | S 6 6 T | S 7

-------- ----------------- -----------------

4 9 I | R 8 8 I | R 9

-------- ----------------- -----------------

5 11 G | N 10 10 G | N 11

-------- ----------------- -----------------

S 6 | |

-------- ::::::::::::::::: :::::::::::::::::

T 7 65533 | 65532 65532 | 65533

-------- ----------------- -----------------

R 8 65535 | 65534 65534 | 65535

-------- ----------------- -----------------

I 9 (b) (c)

--------

N 10 --------

G 11 -------- 12

--------

::::::::

65534

--------

65535

(a)

a. byte-addressable memory for an 8-bit processor.

b. byte-addressable memory for a 16-bit processor (a so-called “Little Endian” such as the Intel 8086).

c. byte-addressable memory for a 16-bit processor (a “Big Endian” such as the Motorola 68000).

IDE disks

This section gives an overview of how an IDE disk is organised and accessed.

Surfaces

The disk is made up of a number of surfaces

on each of which there is a disk head, set up to read it.

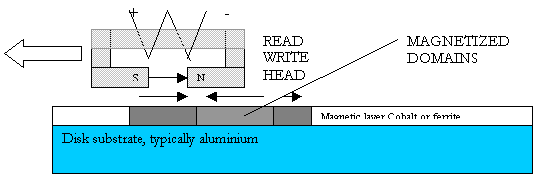

Figure 5 Disk Surface being written

At any one time, information can only be read from one diskhead.

This limitation stems from the means by which heads are positioned on tracks. The tracks are very narrow, and, due to flexing and thermal expansion, servos are required to keep heads above the tracks. Since there is only one disk head actuator, one can not ensure that more than one head at a time is precisely centered on a track.

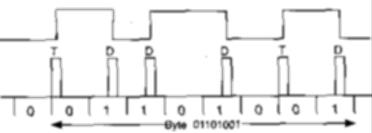

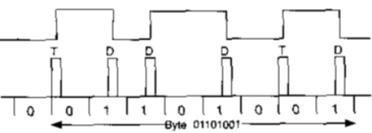

Figure 6 FM disk encoding used in early floppies

• Figure 7 MFM encoding used in modern floppies

Note that MFM encoding uses fewer timing transitions, thus for a given number of flux domains it can store more bits.

cylinders

The heads all move in synchrony under the influence of a single positioning mechanism. This moves the complete set of heads so that they are all above the same track on the corresponding surfaces. The set of tracks that can be read with the heads in a given position is termed a cylinder

tracks and sectors

start of

track mark

SYNC: 10 byte 00

IAM: 2 byte a1 fc

GAP 1: 11 byte 4e

The tracks are divided into a number of sectors. Each sector contains labels which identify it, along with error correction information. A typical sector contains 512 bytes of useable data.

disk sector

SPD: 7 byte 4e

SYNC: 10 byte 00

IDAM: 2 byte a1 fe

ID: 4 byte cyl head sec flag

ECC: 4 byte ECC value

GAP 2: 5 byte 00

SYNC: 10 byte 00

DAM: 2 byte a1 f8

data: 512 data byte

ECC: 4 byte CRC value

GAP 3: 15 byte 00

End of track mark

GAP 4: about 56 bytes of 00

The IDE cable

IDE disks communicate with the computer using a 40 way cable that is a logical extension of the ISA bus, containing a subset of the bus signals.

Table 1 IDE interface

|

Dir |

IDE signal |

Pin |

Signal meaning |

|

o |

RESET |

1 |

reset drives |

|

b |

GND |

2 |

ground |

|

b |

DD7 |

3 |

data bus bit 7 |

|

b |

DD8 |

4 |

data bus bit 8 |

|

b |

DD6 |

5 |

data bus bit 6 |

|

b |

DD9 |

6 |

data bus bit 9 |

|

b |

DD5 |

7 |

data bus bit 5 |

|

b |

DD10 |

8 |

data bus bit 10 |

|

b |

DD4 |

9 |

data bus bit 4 |

|

b |

DD11 |

10 |

data bus bit 11 |

|

b |

DD3 |

11 |

data bus bit 3 |

|

b |

DD12 |

12 |

data bus bit 12 |

|

b |

DD2 |

13 |

data bus bit 2 |

|

b |

DD13 |

14 |

data bus bit 13 |

|

b |

DD1 |

15 |

data bus bit 1 |

|

b |

DD14 |

16 |

data bus bit 14 |

|

b |

DDO |

17 |

data bus bit 0 |

|

b |

DD15 |

18 |

data bus bit 15 |

|

p |

GND |

19 |

ground |

|

|

|

20 |

pin 20 mark |

|

i |

DMARQ |

21 |

DMA request |

|

p |

GND |

22 |

ground |

|

o |

DIOW |

23 |

write data via I/0 channel |

|

p |

GND |

24 |

ground |

|

o |

DIOR |

25 |

read data via I/0 channel |

|

p |

GND |

26 |

ground |

|

i |

IORDy |

27 |

I/0 access complete (ready) |

|

i |

SPSYNC |

28 |

spindle synchronization |

|

o |

DMACK |

29 |

DMA acknow ledge |

|

p |

GND |

30 |

ground |

|

i |

INTR Q |

31 |

interrupt request |

|

i |

IOCS16 |

32 |

indicates 16 bit transfer |

|

o |

DA1 |

33 |

address bus 1 |

|

i |

PDIAG |

34 |

passed diagnostic from slave |

|

o |

DAO |

35 |

address bus 0 |

|

o |

DA2 |

36 |

address bus 2 |

|

o |

CS1Fx |

37 |

chip select for base addr. 1f0 |

|

o |

CS3Fx |

38 |

chip select for base addr. 3f0 |

|

i |

DASP |

39 |

drive activelslave present |

|

p |

GND |

40 |

ground |

Partitions

Figure 8 Partitions and partition

table

Parallel printer interface

Table 2 Parrallel printer interface

|

25 pin |

36 pin |

Signal |

Description |

|

1 |

1 |

strobe |

low signal level transmits data to printer |

|

2 |

2 |

DO |

data bit 0 |

|

3 |

3 |

Dl |

data bit 1 |

|

4 |

4 |

D2 |

data bit 2 |

|

5 |

5 |

D3 |

data bit 3 |

|

6 |

6 |

D4 |

data bit 4 |

|

7 |

7 |

D5 |

data bit 5 |

|

8 |

8 |

D6 |

data bit 6 |

|

9 |

9 |

D7 |

data bit 7 |

|

10 |

10 |

-ack |

low level indicates that printer received |

|

|

|

|

one character and is able to receive more |

|

11 |

11 |

BSY |

high level of signal indicates |

|

|

|

|

- character received |

|

|

|

|

- printer buffer full |

|

|

|

|

- printer initialization |

|

|

|

|

- printer offline |

|

|

|

|

- printer error |

|

12 |

12 |

PAP |

high level indicates out of paper |

|

13 |

13 |

select |

high level indicates that printer is on-line |

|

14 |

14 |

-LF |

auto line feed; low level indicates that |

|

|

|

|

printer issues line feed automatically |

|

15 |

32 |

-err |

low level indicates |

|

|

|

|

- out of paper |

|

|

|

|

- printer offline |

|

|

|

|

- printer error |

|

16 |

31 |

-init |

low level initializes printer |

|

17 |

36 |

-selectIn |

low level selects printer |

|

18-25 |

19-30,33 |

ground |

ground 0 V |

|

|

16 |

logical ground |

0v |

|

|

17 |

case |

protective ground of case |

|

|

18 |

not used |

+5V |

|

|

34 |

unused |

|

|

|

35 |

unused |

pulled to 5v by 4.7kOhm resistor |

V24 or Rs232 Interface

Serial transmission

Bits sent 1 at a time over a single line. One clock cycle per bit.

Two types of serial transmission, synchronous and asynchronous.

Synchronous

Clock signal sent with the data

Bytes transmitted in a continuous stream

Synchronisation chars sent first

![]() Figure 9 synchronoous serial packet

Figure 9 synchronoous serial packet

Clock signals generated locally at receiver and transmitter from quartz crystal oscillators.

These clocks are synchronised by a start bit at the beginning of every character.

Figure 10 Asynchronous serial

transmission

Error conditions

Overrun

Overrun error: if data is arriving in the receiver faster than it is read from the receiver buffer register by the CPU, then a later received byte may overwrite the older data not yet read from the buffer. This is called an overrun error.

Parity

Parity error: if none of the above indicated errors has occurred and the byte has been received seemingly in a correct form, a parity error may still be present, that is, the calculated parity doesn’t coincide with the set one.

Parity of a character is computed using the xor of all of its bits.

Parity can be set to be even or odd by manipulating the top bit of the byte. With even parity this is set to ensure that the xor of all 8 bits is 0, with odd parity that the xor of all 8 bits is 1.

Table 3 Examples of parity

|

Char |

Binary 7 bit char |

XOR of char |

8 bits with even parity |

8 bits with odd parity |

|

A |

100 0001 |

0 |

0100 0001 |

1100 0001 |

|

B |

100 0010 |

0 |

0100 0010 |

1100 0010 |

|

C |

100 0011 |

1 |

1100 0011 |

0100 0011 |

|

W |

101 0111 |

1 |

1101 0111 |

0101 0111 |

Physical standard

The standard defines the mechanical, electrical, and logical interface between a data terminal equipment (DTE) and a data carrier equipment (I)CE). The DTE is the computer , the DCE is the modem. The RS-232C standard defines 25 lines between DTE and DCE, and thus a 25-pin plug. Most are reserved for a synchronous data transfer and are not used for on PCs. For Asynchronous transfer only eleven of the RS-232C signals are required. IBM defines a 9-pin connection for its serial interface, where two of the usually present RS232C lines are missing. Table shows the corresponding signals for 25 and 9-pin plugs.

|

25 pin |

9 pin |

Signal |

Direction |

Description |

|

1 |

- |

|

|

protective ground |

|

2 |

3 |

TD |

PC ®MODEM |

transmitted data |

|

3 |

2 |

RD |

MODEM ® PC |

received data |

|

4 |

7 |

RTS |

PC ®MODEM |

request to send |

|

5 |

8 |

CTS |

MODEM ® PC |

clear to send |

|

6 |

6 |

DSR |

MODEM ® PC |

data set ready |

|

7 |

5 |

|

|

signal ground (common) |

|

8 |

1 |

DCD |

MODEM ® PC |

data carrier detect |

|

20 |

4 |

DTR |

PC ®MODEM |

data terminal ready |

|

22 |

9 |

RI |

MODEM ® PC |

ring indicator |

|

|

|

|

|

|

You should understand the following control signals between PC and MODEM

RTS (Request to Send): The PC asks the MODEM if it can send a byte.

CTS (Clear to Send): this signal from the MODEM is a reply to RTS and indicates that the PC can output data.

DCD (Data Carrier Detect): the MODEM activates the DCD signal to show that it has recieved a valid transmission frequency from the remote site - typically the internet ISP.

DSR (Data Set Ready): MODEM tells the PC it is switched on, and has finished any initial exchange of messages with the remote modem.

DTR (Data Terminal Ready): the signal from the PC indicates the PC is switched on and capable of communicating with the modem. If this goes down the modem hangs up the telephone call.

The RI (ring indicator) signal informs the PC that a ring has occurred on the phone line going into the MODEM. If you set up your computer to allow remote logins this is used to alert the computer that an incomming call is occurring.

The major structural components of a CPU are:

· Control Unit: Controls the operation of the CPU

· Arithmetic and Logic Unit: Performs the computer’s data processing functions

· Registers: Provides storage internal to the CPU

· CPU Interconnection: Some means of communication between the CU, ALU, and registers.

The function of the CPU is to:

· Fetch Instructions

· Interpret Instructions

· Fetch data (if required)

· Process data (if required)

· Write data (if required)

Register Organisation

The registers in the CPU serve two functions:

User-Visible Registers: These enable the programmer to minimise external memory references by optimising usage of registers.

Control and Status Registers: These enable the CU to control the operation of the CPU.

User-Visible Registers

These can be categorised as follows:

General Purpose

Data

Address

Condition Codes

In some m/cs General Purpose registers may either be used for Data or Address. In a completely orthogonal IS any GP register can contain the operand(s) for any opcode. Often, however, there are restrictions.

Control and Status Registers

These, in general, are not visible to the user.

Two registers are essential to instruction execution:

Program Counter (PC): Contains the address of an instruction to be fetched.

Instruction Register (IR): Contains the instruction most recently fetched.

All CPU designs include a register often called the Program Status Word (PSW) that contains status information such as condition codes plus other status information.

Pentium

The Pentium is a 32 bit processor. It has 8 x 32 bit general purpose registers organised as follows:

+-----------------+

| eax |

+-----------------+

| ebx |

+-----------------+

| ecx |

+-----------------+

| edx |

+-----------------+

| ebp |

+-----------------+

| ebx |

+-----------------+

| esi |

+-----------------+

| edi |

+-----------------+

16/32 bit use

To retain backward compatibility with the previous 16 bit processors produced by intel , 8086 and 80186, 80286, the intel 32 bit processors (80386, 80486, P5, P6) allow you to use the lower 16 bits of each general purpose register as a 16 bit register. These are then known as the AX as opposed to EAX, BX as opposed to EBX register etc. You can at all times continue to use the processor as a 32 bit machine when writing assembler language by specifying the full register name EAX etc. Since, however, we will be writing DOS programs which, for compatibility have to run on older 16 bit intel processors, we will in the exercises use mainly the lower 16 bits of the registers.

3.1.1 Accumulators

15......87......0

AH

AL

<------AX------>

BH

BL

<------BX------>

CH

CL

<------CX------>

DH

DL

<------DX------>

3.1.2 Index Registers

BP

SP

SI

DI

3.1.3 Segment Registers

CS

SS

DS

ES

3.1.4 Status and Control

IP

D I T S Z A P C Flags

The Data Registers

Four registers, named data registers or general purpose registers (GPR), can be used to hold working variables, constants and counters for use in arithmetic and logical calculations. Although they are 16 bits in size they can be used for operations on 8-bit BYTE or 16-bit WORD data. Thus:

15......87......0

AX

<-byte->

<-----word----->

Data Register

Format

Each

GPR has special attributes:

AX (accumulator). AX is called the accumulator register because it is favoured by the CPU for arithmetic operations. Other operations are also slightly more efficient when performed using AX.

BX (base). In addition to the usual GPR functions, BX has special addressing abilities. It can hold a memory address that points to another variable. Three other registers with this ability are SI, DI, and BP.When using the processor in 32 bit mode, any of the 8 GPRs can be used to hold addresses.

CS (counter). This acts as a counter for repeating or looping instructions. Such instructions automatically repeat and decrement CX and quit when it equals 0.

DX (data). This has a special role in multiply and divide operations. E.g. in multiply it holds the high 16 bits of the product.

The Segment Registers

The CPU contains four segment registers, used as base locations for program instructions, data, and stack. In fact, all references to memory on the PC involve a segment register used as a base location.

CS (code segment). Base location of all executable instructions (code) in a program.

DS (data segment). Default base location for variables.

SS (stack segment). Contains the base location of the stack.

ES (extra segment). An additional base location for memory variables.

The Index Registers

Index registers contain the offsets of variables. The term offset refers to the distance of a variable, label, or instruction from its base segment. Index registers speed up the processing of strings, arrays, and other data structures containing multiple elements.

SI (source index). Takes its name from the string movement instructions in which the source string is pointed to by the SI register. It usually contains an offset value from the DS register, but it can address any variable.

DI (destination index). This acts as the destination for string movement instructions. It usually contains an offset value form the ES register, but it can address any variable.

BP (base pointer). Contains an asumed offset from the SS register as does the stack pointer. BP is often used by a subroutine to locate variables that were passed on the stack by a calling program.

Special Registers

The IP and SP registers are grouped together here, since they do not fit into any of the previous categories.

IP (instruction pointer). IP always contains the offset of the next instruction to be executed. CS and IP combine to form the complete address of the next instruction to be executed.

SP (stack pointer). SP contains the offset, or distance from the beginning of the stack segment to the top of stack. SS and SP combine to form the complete top-of-stack address.

Flags Registers

The Flags register is a special 16-bit register with individual bit positions assigned to show the status of the CPU or the results of arithmetic operations. Each relevant bit position is given a name; other positions are undefined:

Bit position

15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

x x x x O D I T S Z x A x P x C

0 = overflow S = sign

D = Direction Z = Zero

I = Interrupt A = Auxiliary Carry

T = Trap P = Parity

x = undefined C = Carry

The primary memory of the I8086 is based on byte storage elements addressed by an address bus. In many ways this memory can be treated as if it were data or address registers - albeit more inefficiently. Although the memory is byte addressable it can also be used to store word data by using two bytes. However, word data must be addressed (accessed) on even byte boundaries. Word values are stored with their LSB first followed by the MSB. Diagrams that show memory contents will show memory organised into 16-bit words each of which is made up of two bytes. Thus:

Memory Address Contents

--------1000 41 01

--------

1002 30 31

--------1004 00 2A

--------1006 2F 2B

--------4.0.1.1.1.1 The above memory contents could be interpreted as:

1) Byte values 41 01 30 31 00

at address 1000 1001 1002 1003 1004

2) Word values 0141 3130 2A00 2B2F

at address 1000 1002 1004 1006

3) Combinations of (1) and (2)4) A series of instructions in machine code.

Memory Map of a PC

------------------------------- ^

00000 Interrupt Vector Table |

------------------------------- |

00400 DOS Data Area |

------------------------------- |

Software BIOS |

DOS Kernel, Device Drivers, etc. 640K

Resident part of COMMAND.COM RAM

------------------------------- |

|

Available RAM for transient |

programs |

|9FFFF Transient part of COMMAND.COM v

-------------------------------A0000 EGA/VGA Graphics Buffer -------------------------------B0000 MDA Text Buffer -------------------------------B8000 CGA/EGA/VGA Text Buffer -------------------------------C0000 Reserved

-------------------------------F0000 ROM BIOS

-------------------------------FFFFF (end of address space)

Map of the first megabyte of PC memory

Map of the first megabyte of PC memory

The I8086 can address 1,048,576 bytes of memory (1MB) using a 20-bit address (00000-FFFFF) in what is termed real address mode. The memory is divided between RAM - starting at location 00000 and extending to BFFFF - and ROM - C0000 to FFFFF.

Under DOS, only the first 640K RAM is available for programs. The remaining address space is used by system hardware such as the video display and hard disk controller or by the ROM BIOS ( a firmware portion of DOS).

Video Display

The video display is memory-mapped. This means that each screen position has its own separate address. When DOS writes a character to the display, it calls a subroutine in the ROM BIOS, which in turn write the character directly to the video memory address.

Video RAM varies between 4KB and 1MB in size. For high-resolution VGA colour displays, the amount of memory used (128KB - 1MB) depends on the number of simultaneous colours supported by the video controller card. The monochrome display uses only 4KB, starting at B0000. All other displays are based at location B8000.

Programs often write characters directly to the video display buffer because the method is so fast.

Read-Only Memory (ROM)

Locations C0000 to FFFFF are

reserved for specialised ROM uses, including the hard disk controller and ROM

BASIC.

The ROM BIOS - at F0000 to FFFFF is

the fundamental building block of the PC’s operating system. It contains system

diagnostic and configuration software, as well as the low-level I/O subroutines

used by DOS.

Purpose of the debugger

examine programs

examine files

low level debugging of programs

patch files

disassemble programs

assemble short code fragments

examine system memory

Invoking the debugger

Typing:C:\WINDOWS>debugProduces the outputaddress 16 bytes of data in hex format ascii data• d3C09:0100 0F 00 B9 8A FF F3 AE 47-61 03 1F 8B C3 48 12 B1 .......Ga....H..3C09:0110 04 8B C6 F7 0A 0A D0 D3-48 DA 2B D0 34 00 F8 3B ........H.+.4..;3C09:0120 00 DB D2 D3 E0 03 F0 8E-DA 8B C7 16 C2 B6 01 16 ................3C09:0130 C0 16 F8 8E C2 AC 8A D0-00 00 4E AD 8B C8 46 8A ..........N...F.3C09:0140 C2 24 FE 3C B0 75 05 AC-F3 AA A0 0A EB 06 3C B2 .$.<.u........

Addresses are made up of two portions ssss:dddd where ssss specifies the segment and dddd the offset within segment. These map to physical addresses using the rule: physical address = 16 * segment + offset hence

3c09:0100 maps to0100

3c0903c190

On the x86 family addresses in segment:offset form have a many to one mapping onto physical addresses. eg:

14c1:0100 = 14c0:0110 = 12b1:22000110

14c0014d10 2200

12b1014d10

Note that the display command starts at address 100 hex by default. The segment address denotes the start of free memory. This will vary with the system configuration.

We can display another area of memory by parameterising the d command:

• d 03C09:0000 CD 20 BC 2F 00 9A EE FE-1D F0 4F 03 6D 36 8A 03 . ./......O.m6..3C09:0010 6D 36 17 03 6D 36 97 07-01 01 01 00 02 FF FF FF m6..m6..........3C09:0020 FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF-FF FF FF FF 1D 29 E6 FF .............)..3C09:0030 3B 29 14 00 18 00 09 3C-FF FF FF FF 00 00 00 00 ;).....

That still operated on segment 3c09, we can chose another segment thus:

• d 10:200010:0020 97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0-97 EA 00 F0 B2 0C E3 FE ................0010:0030 97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0-97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0 ................0010:0040 97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0-97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0 ................0010:0050 97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0-97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0 ................0010:0060 97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0-97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0 ................0010:0070 05 00 F4 30 97 EA 00 F0-97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0 ...0............0010:0080 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00-00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................0010:0090 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00-00 00 00 00 40 00 E1 30 ............@..0

By default the debugger displays a 128 byte section of memory following the address you supply, you can get it to display more or less by specifying a range. The syntax is

d ssss:bbbb,eeeewheressss Segment numberbbbb begining offseteeee end offset

Example:

• d 10:20,300010:0020 97 EA 00 F0 97 EA 00 F0-97 EA 00 F0 B2 0C E3 FE ................0010:0030 97 .

Examining a File

enter some data into a file using an editor.

C:\TMP>edit tempC:\TMP>debug temp• d3C09:0100 54 68 69 73 20 69 73 20-61 20 74 65 6D 70 6F 72 This is a tempor3C09:0110 61 72 79 20 66 69 6C 65-20 63 61 6C 6C 65 64 20 ary file called3C09:0120 74 65 6D 70 0D 0A 77 69-74 68 20 74 77 6F 20 6C temp..with two l3C09:0130 69 6E 65 73 20 6F 66 20-74 65 78 74 20 69 6E 20 ines of text in3C09:0140 69 74 2E 0D 0A 75 05 AC-F3 AA A0 0A EB 06 3C B2 it...u........

The file is displayed in both hex and ascii. Unprintable characters like carriage return (0D) and linefeed (0A) appear as dots.

Modifying memory

This is done with the E for examine command

• e 1003C09:0100 54.41• e 1003C09:0100 41.41 68.42 69.43 73.44-

characters in italic are typed by the user As you type in numbers followed by a space it shows the previous value in that location. If you follow that with a space you move onto the next location. Modification is terminated by pressing a return character.

Registers

registers can be examined and loaded using the r command.

• r ssSS 3C09 printed by the debugger:100 typed in by user• r axAX 0000:12-

The user provides the register mnemonic and the debugger shows its current contents and allows a new value to be typed in. we can then examine the changes in the whole register set by typing r without a parameter

• rAX=0012 BX=0000 CX=0045 DX=0000 SP=FFEE BP=0000 SI=0000 DI=0000DS=3C09 ES=3C09 SS=0100 CS=3C09 IP=0100 NV UP EI PL NZ NA PO NC3C09:0100 41 INC CX

This shows the registers, the flags and the current instruction about to be executed.

Assembly of program fragments

Let us write our first program in machine code: invoke the debugger with ‘a.com’ as a parameter

windows>debug a.com

Use the assemble command a

• a 1003C09:0100 mov ah,2 dos code for print char3C09:0102 mov dl,42 42 is hex for B3C09:0104 int 21 interrupt 21 is DOS3C09:0106 mov ah,0 dos code for halt3C09:0108 int 213C09:010A-

Now disassemble it to check it.

• u 1003C09:0100 B402 MOV AH,023C09:0102 B242 MOV DL,423C09:0104 CD21 INT 213C09:0106 B400 MOV AH,003C09:0108 CD21 INT 21

Write to file and execute

We write the program to file by giving its base address in the bx register, and its length in the cx register and then executing the w command.

• r bxBX 0000:0• r cxCX 0045:10• wWriting 00010 bytes

Quit the

debugger

• q

Display the

program

C:\TMP>dir *.comVolume in drive C is MS-DOS_6Volume Serial Number is 1F5E-6F6DDirectory of C:\TMPA COM 16 03/10/96 15:52 1 file(s) 16 bytes33,636,352 bytes free

run the

program

C:\TMP>aBC:\TMP>

Tracing

You can execute your program a single instruction at a time with the trace command t.

• t 1 AX=0200 BX=0000 CX=0010 DX=0000 SP=FFFE BP=0000 SI=0000 DI=0000DS=3C56 ES=3C56 SS=3C56 CS=3C56 IP=0102 NV UP EI PL NZ NA PO NC3C56:0102 B242 MOV DL,42• t 1 AX=0200 BX=0000 CX=0010 DX=0042 SP=FFFE BP=0000 SI=0000 DI=0000DS=3C56 ES=3C56 SS=3C56 CS=3C56 IP=0104 NV UP EI PL NZ NA PO NC3C56:0104 CD21 INT 21• t 1 AX=0200 BX=0000 CX=0010 DX=0042 SP=FFF8 BP=0000 SI=0000 DI=0000DS=3C56 ES=3C56 SS=3C56 CS=293B IP=60A0 NV UP DI PL NZ NA PO NC293B:60A0 2E CS:293B:60A1 C6069E6000 MOV BYTE PTR [609E],00 CS:609E=00-

Help

You

can obtain help by typing a ?

-?assemble A [address]compare C range addressdump D [range]enter E address [list]fill F range listgo G [=address] [addresses]hex H value1 value2input I portload L [address] [drive] [firstsector] [number]move M range addressname N [pathname] [arglist]output O port byteproceed P [=address] [number]quit Qregister R [register]search S range listtrace T [=address] [value]unassemble U [range]write W [address] [drive] [firstsector] [number]-

3.2

The assembler

The assembler that we will be

using is called A86. It is invoked from the command line using a single line

command:

c>A86 myfile.asm

This generates a new file

myfile.com, which is binary executable program. The program can be invoked by

typing the name of the program file:

c>Myfile

Use the assembler for all

longer or more complicated programs, the debugger is only suitable for

assembling very short programs.

The lowest 1024 byte of memory (00000 - 003FF) contain the interrupt vector table. These are addresses used by the CPU when processing hardware and software interrupts.

The software BIOS includes routines for managing the keyboard, console, printer, and time-of-day clock. These routines come from a hidden system file on every boot disk called IO.SYS.

The DOS kernel is a collection of DOS services that may be called by application programs and are contained in another hidden file called MSDOS.SYS.

Above this kernel resides both file buffers and installable device drivers (loaded from the CONFIG.SYS file) followed by the resident part of COMMAND.COM - the DOS command processor: It interprets commands typed at the DOS prompt and loads and initiates the execution of programs.

PC Boot-Up

Procedure

When a PC is booted (started), the following happens: THe CPU jumps to an initialisation program in the ROM BIOS. A program called the bootstrap loader loads the boot record from a disk. The boot record contains a program that executes as soon as it is loaded. This program in turn loads IO.SYS and MSDOS.SYS and, finally, COMMAND.COM.

The resident part of COMMAND.COM remains in memory all the time: it

issues error messages, has routines to process Ctrl-Break and critical errors.

The initialisation part reads the AUTOEXEC.BAT file; it is used only while DOS

is being loaded. The transient part is loaded into high RAM and interprets DOS

commands typed at the keyboard. Finally, COMMAND.COM takes over and acts as an

interpreter for user commands.

An address is a number that refers

to an 8-bit memory location. In the I8086 they are expressed in one of two

hexadecimal formats:

A 32-bit segment-offset address. which combines a base location (segment) with an offset to represent an actual location. E.g. 08F1:0100

7.0.1.1.1.1 A 20-bit absolute address, which refers to an exact memory location. E.g. 09010

Using 20 bits, the CPU can address up to 1,048,576 of memory but address registers are only 16 bits wide and can only hold a maximum value of 65,535. To solve this apparent dilemma, the CPU combines the segment and offset values to create an absolute address. As the (16-bit) segment value is always understood to have 4 implied zero bits to the right to pad its length to 20 bits, a segment address of 08F1 really represents an absolute location of 08F10.

0 8 F 1 (0)

0000 1000 1111 0001 0000 <- 4 implied bits

The CPU then adds the offset to the segment, yielding the absolute address:

Segment value -> 0 8 F 1 (0)

Add the offset -> 0 1 0 0

Absolute address -> 0 9 0 1 0

Tutorial on protected mode addressing

When operating under what is called Protected Mode, as used by Windows, OS/2, or Linux, a Pentium processor has a more sophisticated way of using the segment registers to compute an address.

I have said up to now that the segment registers are 16 bits long. In fact they are 96 bits long on a pentium, of which, only the top 16 bits can be accessed by the programmer. The remaining 80 bits are accessible to the Control Unit of the chip and are used by it to calculate actual addressses in a 32 bit linear address space.

7.0.2 Extended segment registers

A more accurate picture is then:

visible| invisible to program

16 | 16 32 32 widths

+----+----+--------+--------+CS| sel|type| base | limit |

+----+----+--------+--------+SS| sel|type| base | limit |

+----+----+--------+--------+DS| sel|type| base | limit |

+----+----+--------+--------+ES| sel|type| base | limit |

+----+----+--------+--------+FS| sel|type| base | limit |

+----+----+--------+--------+GS| sel|type| base | limit |

+---------------------------+

The visible

part is called the selector. When a memory location is accessed the processor

goes through the following steps Assume we have an address of the form

DS:offset

1. The offset is compared to the DS limit.

2. If it is greater than the limit an error occurs, indicating for instance an attempt to access outside the bounds of an array.

3. If it is less than or equal to the limit, the DS base is added to the offset to yield the memory address to be fetched.

In DOS mode the hardware ensures that the limit is always 0000FFFF and that given a selector SSSS the base field of the register will contain 000SSSS0. This achieves the result described earlier. Under Windows, the operating system can set up the base and limit fields to point anywhere within the machine’s 32 bit linear address space.

7.1

Any program written in a HLL must be translated into machine language in order to be executed. Thus the set of m/c instructions must be sufficient to express any of the instructions from a HLL. Thus we can categorise the following types:

Data Processing: Arithmetic & Logic

Data Storage: Memory instructions

Data Movement: I/O instructions

Control: Test & Branch instructions

Instruction Repertoire - types of operation

The number of different opcodes varies widely from machine to machine. A typical categorisation is:

Data Transfer

Arithmetic

Logical

Conversion

I/O

System Control

Transfer of Control

Instruction Encoding

An I8086 instruction contains a specification of the operation to be performed, the data size to be used, and information on where the data is to be found. The assembly language form of the instruction contains a mnemonic for the operation, an operation size (where necessary to clarify an operand’s type), and operands specifying information on the data used by the operation. For example:

<mnemonic>

<size> <operand>,<operand>

If an instruction requires two operands, the first operand is the source and the second is the destination. An operand is specified by an addressing mode that tells the CPU how to locate the register or memory address containing the data needed by the instruction.

Instruction Representation

Each instruction is represented by a sequence of bits, sub-divided into fields corresponding to the constituent parts of the instruction - INSTRUCTION FORMAT. In general, more than one format is used. For example, in the I8086 the generic form of an instruction is:

opcode mod reg r/m

[7 0 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0]

immed-low immed-high

[7 0 7 0]

disp-low disp-high

[7 0 7 0]

During instruction execution the CPU extracts the data from the various fields to perform the required operation.

The opcode (operation code) field is stored in the lowest byte (at the lowest address). All remaining bytes are optional: the ModR/M field identifies the addressing mode and operands; the immed-low and immed-high specify immediate operands (constants); the disp-low and disp-high fields are for displacements added to base and index registers in the more complex addressing modes. Few instructions will contain all of these fields; on average, most instructions are only 2-3 bytes long.

Opcode. The opcode field identifies the general instruction type (MOV, ADD, SUB, and so on) and contains a general description of the operands.

Many instructions have a second byte - the ModR/M byte - which identifies the type of addressing mode being used. For example, the Intel encoding for a 16-bit MOV from a register to any other operand is:

89 /r

where /r means that a ModR/M byte follows the opcode. The ModR/M byte is made up of three fields:

mod reg r/m

11 011 000 = D8

source dest.

reg or r/m Register reg or r/m Register

000 AX or AL 100 SP or AH

001 CX or CL 101 BP or CH

010 DX or DL 110 SI or DH

011 BX or BL 111 DI or BH

Variables are really just symbolic names for locations in memory where data is stored. In assembly language, variables are identified by labels. A label’s offset is the distance from the start of a segment to the beginning of the variable.

A label does not, however, indicate how many bytes of storage are allocated to a variable - it is, in effect, the address of the first byte of a data structure.

Data definition directives are used to allocate storage based on the following pre-defined types:

Directive Defines Bytes

DB Byte 1

DW Word 2

DD Doubleword 4

DF,DP Far pointer 6

DQ Quadword 8

DT Tenbytes 10

Define Byte

The DB directive allocates storage for one or more 8-bit values. The following syntax diagram shows that label is optional, and only one intialvalue is required. If more are suppied, they must be separated by commas:

[label] DB initialvalue [,initialvalue]

Initialvalue can be one or more 8-bit values, a string constant, a constant expression (evaluated at assembly time), pr a question mark (?). If the value is signed, it has the range -128 to +127; if unsigned, the range is 0 to 255. Here are a few examples:

char db ‘A’ ; ASCII charactermin_s db -128 ; min. signed valuemax_s db +127 ; max. signed valuemin_u db 0 ; min. unsigned valuemax_u db 255 ; max. unsigned value

Each value may also be expressed in a different radix. For example, the following variables all contain exactly the same value. Which radix to use is entirely up to the programmer but is usually chosen to reinforce the context of its use. I.e. if a value is to be treated in a ‘character’ context then the definition reflects that. Thus:

char_version db ‘A’ ; ASCII characterhex_version db 41h ; as hexadecimaldec_version db 65 ; as decimalbin_version db 01000001b ; as binaryoct_version db 101q ; as octal

Note: when a hexadecimal number begins with a letter (A-F), a leading zero is added to prevent the assembler from interpreting it as a label.

[Caveat: DEBUG assumes all values are expressed as hexadecimal and, as it does not allow labels, no leading zero is required.]

A list of values may be grouped under a single label, with the values separated by commas. In the following example, list1 and list2 have the same contents:

list1 db 10, 32, 41h,001000010blist2 db 0Ah,20h,’A’,22h

A variable contents may be left undefined by using the question mark

(?) operator. Or a numeric expression can initialise a variable with a value

that is calculated at assembly time. Examples:

count db ?ages db ?,?,?,?,?scrn_size db 80*24

A string may be assigned to a variable, in which case the variable (label) stands for the address of the first byte.

C_string db “Good morning”,0

pascal_string db 12,”Good morning”

Long strings can be made more readable in an AL source program by continuing them over multiple lines without the necessity of supplying a label for each. The following string is terminated by an end-of-line sequence and a null byte:

a_long_string db “This is a string “ db “that clearly is going to take “ db “several lines to store in an “ db “assembly language program.” db 0Dh,0Ah,0 ; EOL sequence + NULL

The assembler can automatically calculate the length of a string by making use of the $ operator which represents the assembler’s current location counter value. In the following example, a_string_len is initialised to 16:

a_string db “This is a string”

a_string_len db $-a_string

A DEBUG Example. Using DEBUG, we can practice defining bytes and moving them between registers and memory. Remember, however, the restriction that labels cannot be used, so that all references to memory must be a numeric address enclosed in brackets. For example:

Statement Comment

A 150 Assemble data at offset 150

db 10,0 Define 2 data bytes

<ENTER> ends assembly

A 100 Assembly code at offset 100h

mOv ax,0 Clear the AX register

mov ah,[150] Move data to AH

add ah,10 Add 10 to AH

mov [151],ah Store AH in memory

int 20 End program

<ENTER> ends assembly

T Trace each instruction

T T T D 150,151 Dump memory at 150-151

Define Word

The DW directive creates storage for one or more 16-bit words. The syntax is:

[label] DW initialvalue

[,initialvalue]

Initialvalue can be any 16-bit value from 0 to 65,535 (FFFFh) or -32,768 (8000h) to +32,767 (7FFFh) if signed, a constant expression (evaluated at assembly time), or a question mark (?) to leave a variable uninitialised.

Reversed Storage Format. The assembler reverses the byte in a word value when storing them in memory - little-endian format; the lowest byte occurs at the lowest address. When the variable is moved to a 16-bit register, the CPU reverses the bytes.

Pointers.

The offset of a variable or subroutine may be stored in another variable. In

the next example, the assembler sets listPtr to the

offset of list. Then listPtrPtr

contains the address of listPtr. Finally, aProcPtr

contains the offset of a label called clear_screen.

list dw 256,257,258.259

listPtr dw list

listPtrPtr dw listPtr

aProcPtr dw clear_screen

A DEBUG Example. Using DEBUG, we can practice defining words and moving them between registers and memory. For example:

Statement Comment

A 150 Assemble data at offset 150

dw 1234,5678 Define 2 data words

<ENTER> ends assembly

A 100 Assembly code at offset 100h

mov ax,[150] Move 1234 to AX

mov bx,[152] Move 5678 to BX

add ax,2 AX := 1236

mov [154],ax Store 1236 at offset 154

mov [150],bx Store 5678 at offset 150

int 20 End program

<ENTER> ends assembly

T Trace each instruction

T T T T

D 150,155 0150: 78 56 78 56 36 12

Define Doubleword

The DD directive creates storage for one or more 32-bit doublewords. The syntax is:

[label] DD initialvalue

[,initialvalue]

Initialvalue can be any 32-bit value up to FFFFFFFFh, a segment-offset address, a 4-byte encoded real number, or a decimal real number. The bytes are stored in little-endian format, i.e. the value 12345678h would be stored in memory as:

offset: 00 01 02 03

value: 78 56 34 12

You can define either a single doubleword or a list of doublewords. In the example that follows, far_pointer1 is uninitialised and the assembler automatically initialises far_pointer2 to the 32-bit segment-offset address of subroutine1:

signed_val dd -2147483648

far_pointer1 dd ?

far_pointer2 dd subroutine1

DUP Operator

The DUP operator only appears after a storage allocation directive (DB, DW,...). DUP allows for the repetition of one or more values when allocating storage. This is especially useful when allocating space for a table or array. For example:

db 20 dup(0) ; 20 bytes, all zeroed

db 20 dup(?) ; 20 uninitialised bytes

db 4 dup(‘ABC’) ; 12 bytes: ‘ABCABCABCABC’

The DUP operator may also be nested. The first example below creates storage containing (in ASCII) 000XX000XX. The second example creates a 2-dimensional word table of 3 rows by 4 columns:

aTable db 4 dup( 3 dup(‘0’), 2 dup(‘X’) )

anArray dw 3 dup( 4 dup(0) )

Type Checking. When a variable is created using DB, DW, etc., the assembler gives it a default attribute (byte, word, etc.) based on its size. This type is checked on referencing the variable and an error results if the types do not match. So:

count dw 20h

...mov al,count ; error: operand sizes must match

To overcome type checks requires the use of a LABEL directive to create a new name (and associated type) at the same address. Thus:

count_low label byte ; byte attribute

count dw 20h ; word attribute

...mov al,count_low ; retrieve low byte of count

mov cx,count ; retrieve all of count

9.0

9.0.1.1.1.1

Created on 25 Oct

1995

3.2.1.1.1.1.1.1.1 Duncan Smeed <duncan@cs.strath.ac.uk>

3.2.1.1.1.1.1.1.2 Updated 1 Oct by Paul Cockshott wpc@dcs.gla.ac.uk

3.2.1.1.1.1.1.1.3 Updated further by Paul Cockshott Jan 2000

Typically, an Assembly Language Program (ALP) is divided into three sections that specify the main components of a program. In some cases these sections can be inter-mixed to provide for better design and structure.

Assembler Directives (aka Pseudo-ops)

These are instructions supplied by the user to the assembler for defining data and symbols, setting assembler and linking conditions, and specifying output formats, etc. The directives do not produce machine code.

Assembly Language Instructions

These are the actual I8086 instructions.

Data Storage Directives

These allocate data storage locations containing initialized or uninitialized data.

Such mnemonics are not converted into machine code but are directives to the actual assembler. For example:

DOSSEG - Specifies a standard segment order for the code, data and stack segments.

PROC - Identifies the first executable instruction: the program entry point.

END - Program End. This informs the assembler that the program source is finished.

These are converted by the assembler into the equivalent machine code instructions. For example:

MOV - to move data, i.e. memory to register

ADD - to add two data values

AND - to logically AND two data values

In general an AL statement can contain up to four fields. Namely:

[name]

[mnemonic] [operands] [comment]

[Name]

A name identifies a label, variable, symbol or keyword.

Variable and Constants. A name used before a memory allocation directive identifies a location where data are stored in memory. One may also use a name to define a constant, as shown below:

count1 db 50 ; a variable

max_col equ 80 ; a constant

Label If a name appears next to a program instruction, it is called a label. Labels serve as place markers whenever a prgram needs to jump or loop from one location to another.

Keyword A keyword, or reserved word, always has some predefined meaning to the assembler. It may be an instruction or it may be an assembler directive. Examples are MOV, PROC, ADD, AX, and END. Keywords cannot be used out of context or as identifiers. For example, the use of add as a label is illegal:

add: mov ax,10

Rules for Valid Names

These vary from assembler to assembler. Most should accept labels that adhere to the following rules:

The name must start in the first column and be terminated by a :

It may contain six characters, the first of which must be alphabetic and the others alphanumeric*

The name should not be the same as an instruction mnemonic or other reserved words (e.g. ADD, MOV, END, AX)

The name given to the label should be unique within the program.

typical I8086 assemblers for the PC are less restricted than this - e.g. allowing up to 31 character names and including ?_@$. in the set of characters accepted. However, the linker may impose its own restrictions.

[Mnemonic]

This field contains the mnemonic of:

an instruction (e.g. MOV, ADD) or,

a pseudo-op (e.g. PROC, END)

To distinguish labelled statements from unlabelled ones the opcode field of an unlabelled statement must NOT start in the first column.

[Operands]

For those instructions that require operands then this field contains one or more operands separated by commas (e.g. registers or addresses of data to be operated upon by the instruction in the op-code field.

[Comment]

The remainder of the statement is the comment field. Comments in the program are for documentation purposes only and are ignored by the assembler. Some assemblers require this field to start with a special character, such as ‘;’.

Comment-Only Statements

The exception to the format of label, op-code, operand and comment is that if a line starts with a special comment-line character, usually ‘;’, then the whole line is treated as a comment.

Field Separators

In general, the fields are separated by spaces and if the label field is NOT present it must be replaced by at least one space. To improve the appearance of the program it is wise to position the fields at particular column positions (e.g. at tab stops). .For example, contrast the following two programs - one with an untidy layout and the other with a neat layout.

;1) Untidily laid out example program

mov ax,[150] ; Move 1234 to AXmov bx,[152] ;Move 5678 to BXadd ax,2 ;AX := 1236

mov [154],ax ; Store 1236 at offset 154

mov [150], bx ; Store 5678 at offset 150

int 20 ; End program;2) Neatly laid out example programmov ax,[150] ; Move 1234 to AXmov bx,[152] ; Move 5678 to BXadd ax,2 ; AX := 1236mov [154],ax ; Store 1236 at offset 154mov [150],bx ; Store 5678 at offset 150int 20 ; End program

Addressing Modes

As we have seen an instruction consists of

the op-code that tells the process what instruction to perform and,

the operand or address field which tells the processor where to find that data to be operated upon. This address is known as the Effective Address (EA).

To determine the EA, the processor uses one of a number of addressing modes that are defined by the operand field of the instruction. Getting the EA from the addressing mode may be quite simple (e.g. the operand is [the contents of] a data register) or complex (e.g. the operand is in memory, the address of which is contained in an address register).

The I8086 supports a number of addressing modes, shown by the following addressing mode (AM) table. In the table, a displacement is either a number or the offset of a variable. The EA of an operand refers to the offset (distance) of the data from the beginning of a segment. BX and BP are base registers, and SI and DI are index registers. In many instructions the operand can only be specified by certain addressing modes.

Register

AX Effective address (EA) is a register

BL

DI

Immediate

10 EA is that part of the instruction opcode

‘A’ that represents the constant

200h

Direct op1 EA is a displacement

bytelist

[200]

Register Indirect

[bx] EA is the contents of a

[si] base or index register

[di]

Based or Indexed

list[bx] EA is the sum of a base

[si+list] or index register and a displacement

[bp+4]

list[di]

[bp-2]

Base-indexed

[bx+si] EA is the sum of a base register and

[bx][di] an index register

[bp-di]

Base-indexed with displacement

[bx+si+2] EA is the sum of a base register,

list[bx+si] an index register, and a displacement

list[bx][si]

Why are there so many(!) AM? Mainly because they make programming more convenient, especially when manipulating data structures such as arrays. For example, the Base-indexed AM lets you set BX and SI to the row and column offsets, respectively, of any element in the table.

Invariably, when referring to an AM, we also refer to the type of operand used. The use of a register operand, for example, implies the register AM.

Register Operand

A register operand may be any 8-bit or 16-bit register. In general, this AM is the most efficient because registers are part of the CPU and no memory access is required. Some examples using the MOV instruction are:

mov ax,bxmov cl,almov si,ax

Immediate Operand

An immediate operand is a constant expression, such as a number, a character, or an arithmetic expression. The assembler must be able to determine the value of an immediate operand at assembly time. Its value is inserted directly into the machine instruction.

Direct Operand

A direct operand refers to the contents of memory at the offset of a variable. The assembler keeps track of every label, making it possible to calculate the effective address of any direct operand. In the following example, the contents of memory location count are moved into AL:

count db 20

.

.

mov al,count

OFFSET Operator.

When it is necessary to move the offset of a label into a register or variable, the OFFSET operator does the trick. Since the assembler knows the offset of every label as the program is being assembled, it simply substitutes the offset value into the instruction. Assuming that the offset of the variable aWord in the following example is 0200h; the MOV instruction would move 200h directly into BX:

aWord dw 1234

.

.

mov bx,offset aWord; the above assembles as: mov BX,0200

Indirect Operand

When the offset of a variable is placed in a base or index register, the register becomes a pointer to the label. For variable containing a single element this is of little benefit but for a list of elements a pointer may be incremented - within a loop, say - to point to each element.

Example. If we create a string in memory at location 0200h and set BX to the base offset of the string, we can access any element in the string by adding its index to BX. The letter ‘F’ is at index 5 in the following example:

;indices are: 0123456aString db “ABCDEFG”

.

.

mov bx,offset aString ; BX = 200

add bx,5 ; BX = 205

mov dl,[bx] ; DL = ‘F’

Segment Defaults.

If BX, SI, or DI is used, the EA is by default an offset from the DS (data segment) register. BP, on the other hand, is an offset for the SS (stack segment) register. Assuming that the stack segment and data segment are at different locations, the following two statements would have different effects even if the SI and BP registers contained the same values:

mov dl,[si] ; look in the data segmentmov dl,[bp] ; look in the stack segment

If one really must use BP in the data segment, a segment override operator forces the issue:

mov dl,[si] ; look in the data segment

mov dl,ds:[bp] ; ditto

Based and Indexed Operands

Based and indexed operands are basically the same: A register is added to a displacement to generate an EA. The register must be SI, DI, BX or BP. A displacement is either a number or a label whose offset is known at assembly time. The notation may take several equivalent forms:

Register Added to an Offset

mov dx,array[bx]

mov dx,[bx+array]

mov dx,[array+bx]

Register Added to a Constant

mov ax,2[si]

mov ax,[si+2]

mov dx,-2[bp]

mov dx,[bp-2]

Example. If we create an array of bytes in memory at location 0200h and set BX to 5, BX can then be used to access the 6th element of the array (note: array indices start at 0).

;indices: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

array db 00,02,04,08,16,32,64,128,256.

.

mov bx,5mov al,array[bx] ; AL = 32

Based-Indexed Operand

An operand’s EA is formed by combining a base register with an index register. Suppose BX = 202h and SI =6; then the following instuction would calculate an EA of 208h:

mov al,[bx+si]

This technique is often useful for two-dimensional arrays, where BX can address the row and SO the column:

array db 10h,20h,30h,40h,50hdb 60h,70h,80h,90h,A0h

db B0h,C0h,D0h,E0h,F0h

.

.

mov bx,offset array ; point to array

add bx,5 ; select 2nd row

mov si,2 ; select 3rd col

mov al,[bx+si] ; get element

Two base registers or two index registers cannot be combined, so the following would be incorrect:

mov al,[bx+bp] ; error: 2 base regs

mov dx,[si+di] ; error: 2 index regs

Base-Indexed with Displacement

An operands effective address is formed by combining a base register, an index register, and a displacement.

Using the previous two-dimensional array example, we no longer have to set BX to the beginning of the array - we just set BX to the address of the second row relative to the beginning of the table. This makes the code simpler:

array db 10h,20h,30h,40h,50hdb 60h,70h,80h,90h,A0h

db B0h,C0h,D0h,E0h,F0h

.

.

mov bx,5 ; select 2nd row

mov si,2 ; select 3rd col

mov al,array[bx+si] ; get element

A DEBUG Example. The following example program shows how a variety of addressing modes may be used when accessing elements of an array. The array is located at offset 150, and the sum will be stored at offset 153:

Statement Comment

A 150 Assemble data at offset 150

db 10,20,30,0 1st 3 bytes are array, last is sum

<ENTER> ends assembly A 100 Assembly code at offset 100h

mov bx,150 BX points to the array

mov si,2 SI will be an index

mov al,[bx] Indirect operand

add al,[bx+1] Base-offset operand

add al,[bx+si] Base-indexed operand

mov [153],al Direct operand

int 20 End program

<ENTER> ends assembly T Trace each instruction

. .

. D 150,153 Dump array and sum

Created on 25 Oct 1995

Duncan Smeed <duncan@cs.strath.ac.uk>

http://www.cs.strath.ac.uk/CS/Courses/223/OHP28-2E.html

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC “-//W3C//DTD HTML 3.2//EN”>

Paul Cockshott

Low Level Program Control Structures

Most computer algorithms contain decision points where code is conditionally executed depending on the status of program variables. Conditional execution and loop constructs are available in high-level languages. The equivalent constructs in assembly language use branch instructions. This section introduces the various forms of I8086 branch instructions and discusses the low level language implementation of high-level language control constructs.

There are two general categories of low level branch:

Unconditional Transfer. The program branches to a new location in all cases; a new value is loaded into the IP, causing execution to continue a the new address.

Conditional Transfer. The program branches if a certain condition is true. The I8086 provides a wide range of conditional transfer instructions that may be combined to make up conditional logic structures. The CPU interprets true/false conditions based on the contents of the CX and Flags registers.

1.1 JMP Instruction

Syntax: JMP SHORT,NEAR PTR,FAR PTR <label>

Action: Program control passes directly to the instruction located at the address <label>.

Notes 1. The SHORT form jumps to label in the range -128 to +127 bytes from the current location (in the same code segment). I.e. an 8-bit signed value is added to the IP. This is especially useful when coding forward jumps since the assembler does not know the destination address until it assembles that part of the program. For example:

label1: jmp short label2

<up to a few dozen insts here...>

...

label2: jmp label1 ; short used

2. The NEAR PTR form tells the assembler that the destination label is in the same code segment; usually this is assumed.

3. The FAR PTR form is required if the jump is to a label outside the current segment.

1.2 LOOP Instruction

The LOOP instruction is the easiest way to repeat a block of statements a specific number of times. CX is automatically used as a counter and is decremented each time the loop repeats.

Syntax: LOOP <label>

Action: 1 is subtracted from the CX. If CX is greater than zero control transfers to <label> which must be -128 to +127 bytes from the current location. If CX = 0 after having been decremented, no jump takes place and control passes to the instruction following the loop.

1.3 Conditional Processing

The Flags (or Condition Code) Register (CCR)

We have seen that JMP is unconditional in that control is always transferred. Conditional transfers of control are a common requirement, typically of the form (in C):

IF (X == 0) Y = 20 ELSE Y = 30;

To support this the iAPX86 has a word sized register called the FLAGS REGISTER with individual bit positions assigned to control the CPU or show the results of arithmetic operations. For conditional processing we are concerned with the way the Zero, Carry and Sign flags show the results of boolean and comparison instructions:

The Zero bit (flag) is set to 1 if the previous instruction gave a zero result, otherwise its 0

The Sign bit takes on the value of the MSBit of the result (given twos complement). If it is 1 then this indicates a negative result.

The Carry bit is set when the result of an unsigned addition is too large for the destination operand or when a subtraction requires a borrow.

The Overflow bit is set when a signed arithmetic operation generates a result that is out of range.

1.4 Boolean Instructions

Boolean instructions are based on boolean algebra operations. These operations allow modification of individual bits in binary numbers, as summarised in the following table:

|

Operation |

Comment |

|

AND |

Result is 1 only when both input bits are 1 |

|

OR |

Result is 1 when either input is 1 |

|

XOR |

Result is 1 only when the input bits differ |

|

NOT |

Result is the reverse of the input (1 <-> 0) |

The first three instructions perform their operations on two 8-bit or 16-bit operands and place their result in the destination operand.

Syntax AND,OR,XOR destination,source

Their operands must be the same size, and only one of them may be a memory operand.

Examples: Assuming that AL contains 10101010b before executing each of the following instructions, the result that would occur after execution is shown as a comment:

AND AL,00001111b ;AL = 00001010b

OR AL,01010101b ;AL = 11111111b

XOR AL,00001111b ;AL = 10100101b

NOT AL ;AL = 01010101b

1.5 Conditional Jumps

These instructions jump (transfer control to a destination address) according to values in the flags register. Their general syntax is:

Jcond <shortlabel>

If the condition cond is TRUE then control is transferred to the address <shortlabel>, otherwise execution continues to the next instruction in sequence.

Table 1: Jumps Based on Unsigned Comparisons

|

Jcond |

Description |

Flag Condition(s) |

|

JZ |

Jump if Zero |

ZF =1 |

|

JE |

Jump if Equal |

|

|

|

(if op1 == op2) |

|

|

JNZ |

Jump if Not Zero |

ZF = 0 |

|

JNE |

Jump if Not Equal |

|

|

|

(if op1 != op2) |

|

|

JA |

Jump if Above |

CF = 0 and ZF = 0 |

|

JNBE |

Jump if Not Below or Equal |

|

|

|

(if op1 > op2) |

|

|

JAE |

Jump if Above or Equal |

CF = 0 |

|

JNB |

Jump if Not Below |

|

|

|

if (op1 >= op2) |

|

|

JB |

Jump if Below |

CF = 1 |

|

JNAE |

Jump if Not Above or Equal |

|

|

JC |

Jump if Carry |

|

|

|

if (op1 < op2) |

|

|

JBE |

Jump if Below or Equal |

CF = 1 or ZF = 1 |

|

JNA |

Jump if Not Above |

|

|

|

(if op1 <= op2) |

|

|

JCXZ |

Jump if CX = 0 |

CX = 0 |

|

JP |

Jump if Parity even |

PF = 1 |

|

JNP |

Jump if No Parity |

PF = 0 |

Table 2: Jumps Based on Signed Comparisons

|

|

|

|

|

Jcond |

Description |

Flag Condition(s) |

|

JG |

Jump if Greater |

ZF = 0 and SF = OF |

|

JNLE |

Jump if Not Less or Equal |

|

|

|

(if op1 > op2) |

|

|

JGE |

Jump if Greater than or Equal |

SF = OF |

|

JNL |

Jump if Not Less |

|

|

|

(if op1 >= op2) |

|

|

JL |

Jump if Less |

SF != OF |

|

JNGE |

Jump if Not Greater or Equal |

|

|

|

(if op1 < op2) |

|

|

JLE |

Jump if Less or Equal |

ZF = 1 or SF != OF |

|

JNG |

Jump if Not Greater |

|

|

|

if (op1 <= op2) |

|

|

JS |

Jump if Signed |

SF = 1 |

|

JNS |

Jump if Not Signed |

SF = 0 |

|

JO |

Jump if Overflow |

OF = 1 |

|

JNO |

Jump if Not Overflow |

OF = 0 |

Comparison Instructions:TEST and CMP

Before executing a conditional jump instruction, the flag bits must be set by executing a previous instruction in the logic of the program. Often the instruction will be an arithmetic operation that produces some result. Other instructions, such as TEST, permit an explicit test of a register or a memory location.

TEST Instruction

The TEST instruction performs an implied (temporary) AND on the destination operand, using the source operand. The flags are affected but neither operand is changed.

Syntax: TEST destination,source

Action: If any matching bit positions are set in both operands, the Zero flag is cleared. It is particularly valuable when you want to know if individual bits in an operand are set.

CMP Instruction

The CMP instruction performs an implied subtraction of the source operand from the destination operand, but neither operand is actually changed.

Syntax: CMP destination,source

Flag Conditions. Generally only three flags are important outcomes from the instruction:

|

After CMP |

Flag Results |

|

Destination < source |

CF = 1 |

|

Destination = source |

ZF = 1 |

|

Destination > source |

CF = 0, ZF = 0 |

The sense of the comparison and resultant branch is <source> cond <destination>, as in:

CMP AL,’9’ compare AL with ‘9’

JLE LABEL jump to LABEL if

AL LE ‘9’,i.e. AL <= ‘9’

Example of compiling while statements

High-level languages provide constructs for conditional code execution and loops. These constructs translate into comparison and jump instructions in assembly language.

Code generated for WHILE

Suppose that we have the while statement:

while ( C1 ) C2

with the Ci standing for expressions.

The effect of the compiler parsing such a statement is to generate abstract machine code that looks like listing 1.

Listing

1

l1:C1

code

condify

code

jumpt

l3

jump l2

l3:C2

code

jump

l1

l2:

Abstract machine

The code shown in listing 1 is not for any one particular type of CPU. It is an abstract machine code. It abstracts from the details of particular machines. The syntax analyser assumes it is producing instructions for this abstract machine. The abstract machine is a general-purpose computer whose instruction set includes all of the operations necessary to implement the semantics of the language that is being translated. On some computers the operations of the abstract machine can be implemented with single instructions. In others, several real machine instructions may be needed to achieve the same effect as the abstract machine instructions.

What is shown in listing 1 is a fairly simple set of abstract machine instructions that are likely to be available to most machines. A full listing of the instructions executed by the abstract machine is given in 10, but we will give a brief outline of the machine here.

The machine is assumed to have four registers:

PC |

Program Counter points at current instruction. |

GP |

Globals Pointer, points at the start of the global variables |

FP |

Frame Pointer, points at the local variables of a procedure |

SP |

Stack Pointer points at the top of the stack. |

On an 8x86 processor these would be mapped to

PC - IP

SP - SP

FP - BP

GP - DS

There are three areas of store:

CS |

The Code Store holds instructions |

STACK |

This holds variables and temporary results |

HEAP |

This holds objects like arrays, strings or structures. |

All instructions are defined in terms of the effect that they produce on the registers and the stores.

Reverse Polish notation

The abstract machine is a stack machine. That is to say arithmetic instructions operate on the top two words on stack. Consider the following expression:

2+4

This works by placing two words on the stack and then adding them as shown in Figure 1.

Step i ii iii

2 4 6 <- top of stack

2

Figure 1: Adding 2 to 4 on the stack

The abstract machine instructions that do this would be:

llint(2)

llint(4)

add

This form of arithmetic in which the operator comes after its operands is termed reverse Polish notation. It is a particularly easy notation to compile into. The general rule for generating code for any binary expression

|

e1 op e2 |

becomes :

generate code for e1

generate code for e2

generate code for op

Reverse Polish notation combined with a recursive descent compiler will automatically generate the right code for expressions with operators of mixed priorities. The expression:

4+2*3

should yield 10. Given the syntax:

<exp3>::=<exp4>[<addop><exp4>]*

<exp4>::=<exp5>[<multop><exp5>]*

<exp5>::=<int-literal>

we obain the parse shown in table 3.

Table 3: Parse and code generation for 4+2 * 3

Parse |

Code produced |

Stack |

exp3 |

|

... |

exp4 addop exp4 |

|

... |

exp5 addop exp4 |

|

... |

4 addop exp4 |

llint(4) |

... 4 |

4 addop exp5 multop exp5 |

|

... 4 |

4 addop 2 multop exp5 |

llint(2) |

... 4 2 |

4 addop 2 multop 3 |

llint(3) |

... 4 2 3 |

4 addop 2 * 3 |

mult |

... 4 6 |

4 + 2 * 3 |

add |

... 10 |

It is easy to translate these abstract instructions into concrete 8x86 instructions since the 80x86 supports a hardware stack. The previous sequence of instructions would generate:

Listing

2

push

4

push

2

push

3

pop

cx

pop

ax

imul

cx

push

ax ;

x

pop

cx

pop

ax ;

y

add

ax,cx

push

ax

The instructions x and y in the above sequence are strictly speaking redundant, and if the compiler has an optimising phase they should be deleted.

Conditionals

The generation of arithmetic instructions is fairly straightforward since computers always have a set of arithmetic machine codes. Handling boolean operations is more problematic.

Consider the operation < which takes two numbers and returns a truth value. In a high level language like S-algol or Pascal truth values have the type boolean, and are represented in memory by a word which contains some non zero value for true and zero for false. Some modern CPUs like the AMD 29000 have opcodes that directly compute this operation, but older ones like the 80x86 series do not. Instead they have comparison instructions which compare two values and set some CPU flags on the basis of the result. In particular the sign and carry flags are set according to the result of comparison. The 80x86 series then provide jump instructions that will conditionally jump on the flags : JL for Jump Less than, JG for Jump Greater than etc.

Suppose we have the source code

if (a<b) X

we want to generate code something like

Listing

3

push

a

push

b

pop

cx

pop

ax

cmp

ax,cx

jl

label1

jump

label2

label1: ...

code for X

label2:

For this sort of construct the setting of CPU flags is quite efficient as a control mechanism. For boolean assignment this is not so suitable. For the statement

p=

a<b

we

need something like

Listing

4

push

a

push

b

pop

cx

pop

ax

cmp

ax,cx

; code to generate a boolean on the stack

jl

label1

push

0 ;*

jump

label2

label1:

push 1 ;*

;

code to perform the assignment

label2: pop

p

The instructions marked with * have to be inserted to convert the values in the flags into a booleanindexflags!conversion to booleans value on the stack.